Explore our AML Solutions

Discover how our AML solutions can help your business navigate and comply with the everchanging rules and regulations.

Learn MoreOne of the most significant events in the anti-money laundering history of the USA took place with the enactment of the 2020 AML Act (AMLA) on 1 January 2021.

AMLA’s passage was not without obstacles. Congress was forced to override a presidential veto to bring the Act into law, and there remain concerns about data privacy issues. AMLA was passed as an amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021.

The introduction and expansion of AML laws in the US have always been contentious. More than 50 years after the enactment of the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA), it is important to understand the AML history upon which AMLA legislation is built.

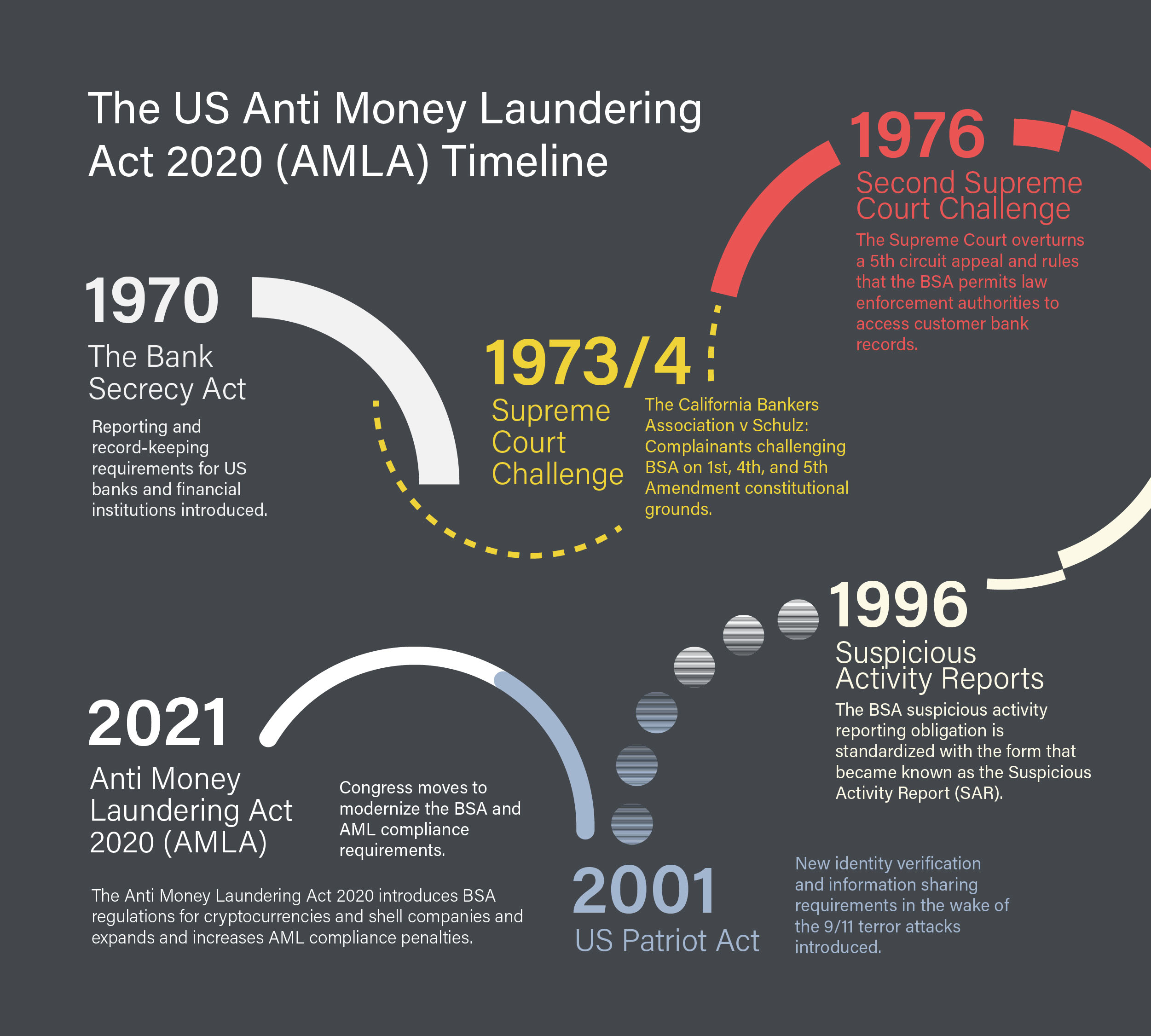

Our US AML Act timeline sets out the most significant moments of AML regulation, from the introduction of reporting and record-keeping requirements in 1970 to the response to terrorism threats and emerging fintech and cryptocurrency risks in the 21st century.

In 1970, Congress passed the Currency and Foreign Transactions Reporting Act – known as the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) – introducing specific record-keeping and reporting obligations for US banks and financial institutions.

The BSA was one of the world’s first pieces of dedicated AML legislation and is still the principal US law for preventing money laundering/terrorist financing (ML/TF), proliferation, and other forms of illicit financial activity. It was introduced in response to the growing trend of criminals using “secret foreign bank accounts” to perpetrate money laundering and other illegal activities – and the inability of US banks to detect and prevent this activity.

Congress held hearings on the details of the BSA before its implementation. Proponents said the BSA would “provide law enforcement authorities with greater evidence” of wrongdoing by collecting information for investigations and proceedings to punish criminals and deter future illegal activity.

The BSA introduced several record keeping and reporting requirements for private individuals, banks, and other financial institutions:

President Nixon signed the BSA into law on October 26, 1970, though it faced constitutional questions and challenges for many years.

The most notable challenge was the California Bankers Association v Schulz, which the US Supreme Court heard in 1973. The challengers claimed that sections of the BSA violated the US Constitution on First, Fourth, and Fifth Amendment grounds.

Their concerns focused on free speech and privacy issues and the extent to which financial institutions could collect and misuse personal information. They also contended that banks were being made to take on “unreasonable burdens” and act as “agents of the government” in the surveillance of private US citizens.

The Supreme Court found in favor of the government in 1974, stating that banks and their customers did not have an “unqualified right to conduct their affairs in secret.” The Court found that many banks were already voluntarily maintaining the records required by the BSA and had submitted currency reports to the US Treasury Department before the BSA’s implementation.

A second significant Supreme Court challenge occurred in 1976 – the United States vs. Miller. In the original bootlegging case, law enforcement authorities had obtained defendant Mitch Miller’s bank records without his consent to secure a conviction. After a 5th Circuit appeal ruled that Miller’s 4th Amendment rights had been violated because a man’s private papers could not be used to establish criminality against him, the US government took the case to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court overturned Miller’s appeal, stating that the defendant had no “legitimate expectation of privacy” in records held by his bank. The Supreme Court held that Miller had effectively revealed his information to a third party when he opened his bank account and that the Constitution did not protect the information disclosed in this context.

Subsequent legislation included:

In 1996, reporting suspicious activity was standardized in an amendment to the BSA. Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) have replaced the criminal referral reporting system since 1984.

While SARs were initially filed on paper, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) – the designated administrator of the BSA – transitioned to online filing in the 21st century. As of April 2013, financial institutions must use FinCEN reports, which are only available electronically through the BSA E-Filing System.

In 1998, the Money Laundering and Financial Crimes Strategy Act required the Department of the Treasury and other agencies to develop a national money laundering financial crimes strategy. It also created the seven High Intensity Financial Crime Areas (HIFCA).

The September 11, 2001 terror attacks saw the US government take steps to detect and prevent the financing of terrorism through the USA Patriot Act. The Patriot Act strengthened and expanded the reporting and record-keeping mandate of the BSA, and the requirement for firms to implement their AML programs, with appropriate internal policies, controls, and procedures.

In enhancing the BSA’s record-keeping requirements, the Patriot Act emphasized the need for firms to verify the identity of the customers with whom they were doing business. It also required them to collect identifying information – such as names, addresses, and dates of birth – and to check that information against international sanctions and watch lists, such as OFAC’s Specially Designated Nationals List (SDNL).

The Patriot Act also introduced new information-sharing requirements between financial institutions and safe-harbor provisions that protected institutions from criminal liability when sharing information for AML/CFT purposes.

The subsequent Intelligence Reform & Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004, amended the BSA to require some financial institutions to report cross-border electronic transmittals of funds if the Secretary of the Treasury decides it is “reasonably necessary” to aid in the fight against ML/TF.

The most recent and significant development in AML/CFT legislation in the US was the passage of the Anti-Money Laundering Act 2020 (AMLA), enacted on 1 January 2021. AMLA strengthens and modernizes the BSA by addressing the money laundering threats posed by shell companies and emerging technologies such as cryptocurrencies. The key BSA provisions of AMLA 2020 include:

The political discourse surrounding the BSA reflects the fundamental importance of financial information to AML/CFT compliance objectives.

While it has been a long road, the BSA has not just led to the introduction of AMLA but has influenced the development of AML/CFT legislation worldwide.

In particular, the regulatory principles of the BSA helped international AML authorities lay the foundations of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) in 1989. Today, FATF defines the global AML/CFT standards while it works to combat emerging ML methodologies and help developing nations enhance their compliance standards.

In June 2021, FinCEN published the first US government-wide list of national AML/CFT priorities and the BSA as part of multi-agency collaboration.

It issued guidance on eight main priorities, including detecting corruption; cybercrime, including relevant cybersecurity considerations and the use of cryptocurrencies; foreign and domestic terrorist financing; fraud; transnational criminal activity; and drug trafficking. Other crimes that must be reported include human trafficking, smuggling, and proliferation financing to acquire weapons of mass destruction.

The priorities – which FinCEN is required to publish under the AMLA – also include crimes that are categorized as “predicate crimes” that generate illicit proceeds that may be laundered through the financial system.

In March 2022, President Biden issued a long-awaited Executive Order (EO) detailing comprehensive plans to create a framework for regulating crypto assets in the US. The EO represented the first whole-of-government approach by the US to address the emerging risks and harness the potential benefits of digital assets and their underlying technology.

The issuance of the EO followed a November 2021 report from the President’s Working Group on Financial Markets, which suggested that stablecoin issuers should be regulated similarly to banks. This coincided with the launch of a new set of sanctions guidelines on the virtual currency industry for financial sector compliance teams by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) the previous month.

In June 2022, the US issued its most comprehensive proposal on regulating crypto assets. The Responsible Financial Innovation Act (or Lummis-Gillibrand Bill – named for its sponsors) plans a comprehensive regulatory framework for digital assets.

The Bill addresses the jurisdiction of the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), tax treatment of digital assets, stablecoin regulation, and interagency coordination. It aims to provide clarity for regulators and the financial industry while delivering the necessary flexibility to operate within the fast-changing virtual asset space.

While changes to AML/CFT legislation in the US have been substantial over the past decades, the shifting global AML landscape and technological innovation mean regulators and financial institutions must be proactive about criminal and terrorist money laundering threats.

For that response to be effective, ongoing, innovative partnership between lawmakers and financial institutions in the US, as well as collaboration with other nations, will be vital to developing new AML laws that remain fit for purpose.

Discover how our AML solutions can help your business navigate and comply with the everchanging rules and regulations.

Learn MoreOriginally published 19 January 2021, updated 12 February 2025

Disclaimer: This is for general information only. The information presented does not constitute legal advice. ComplyAdvantage accepts no responsibility for any information contained herein and disclaims and excludes any liability in respect of the contents or for action taken based on this information.

Copyright © 2025 IVXS UK Limited (trading as ComplyAdvantage).