Russia, Ukraine, and the Torrid 2023 Sanctions Landscape

Financial crime Knowledge & trainingWritten by Alia Mahmud

Alia Mahmud, Regulatory Affairs Specialist at ComplyAdvantage

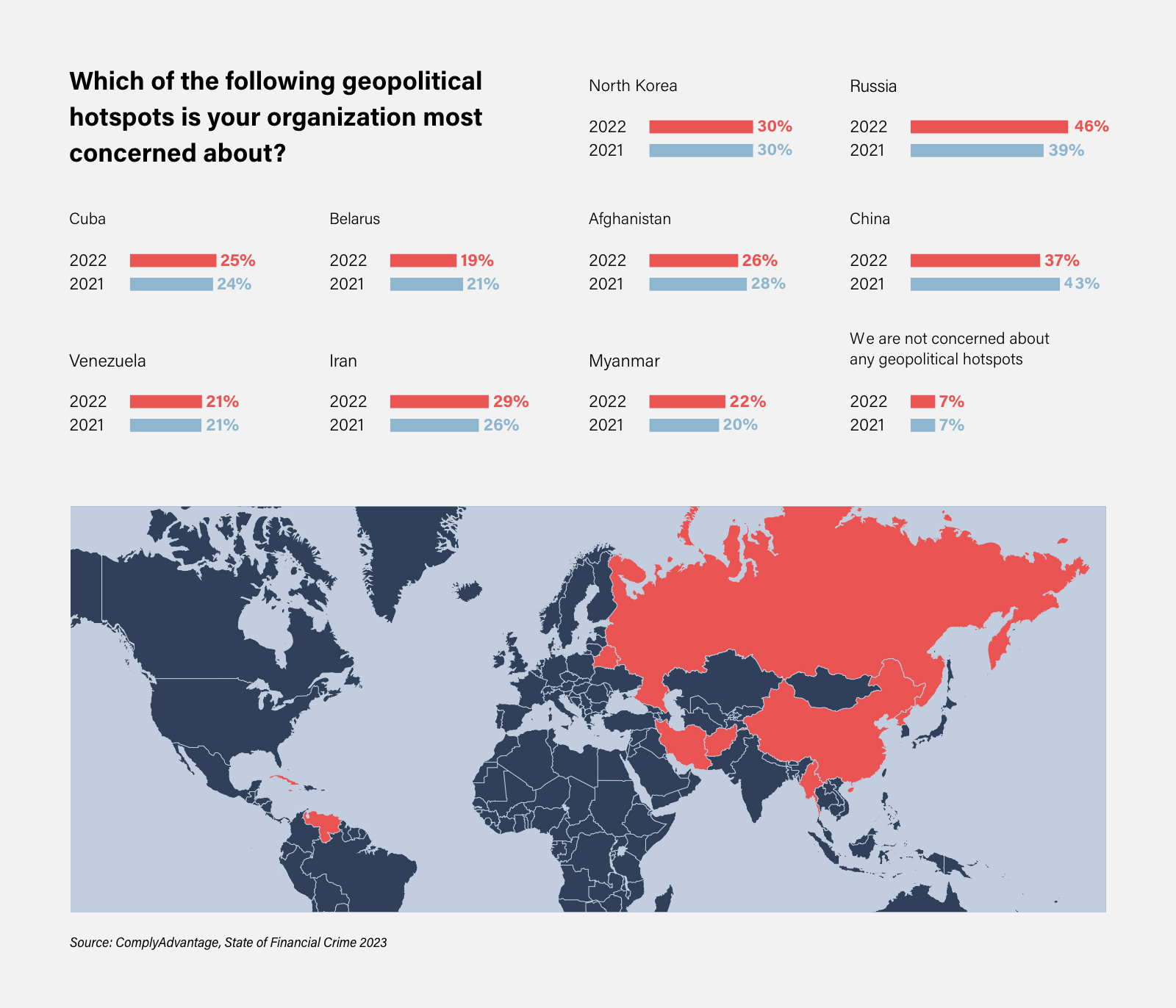

Unsurprisingly, due to the war in Ukraine, Russia topped this year’s list of geopolitical hotspots firms are most concerned about.

The development of sanctions against Russia in 2023 is likely to hinge on developments on the battlefield in Ukraine itself. So far, the Russians have been unable to either topple the Ukrainian government of President Volodomyr Zelenskyy or occupy the country. Moreover, although the Russian military has made territorial gains in the east and south of Ukraine – illegally annexing the Ukrainian regions of Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson, and Zaporizhzhia on September 30, 2022 – Ukrainian forces made several successful counter-offensives. In early November, Russian soldiers were forced to evacuate the city of Kherson in the face of Ukrainian attacks, despite its supposed annexation. At year-end, fighting continued across the east and south of the country, with Russia facing gradual losses of previously gained territory. Its response so far has been to mount drone attacks on energy infrastructure and civilians in the rest of Ukraine, seeking to undermine Ukrainian morale. With Russia unlikely to unambiguously ‘win’ or quit, the conflict will continue into 2023.

How will this affect western sanctions? It seems improbable that there will be any further EU move on natural gas supplies or an attempt to remove all Russian financial institutions from the international financial architecture unless prompted by a major escalation in Russian violence. New sectoral categories will probably be added in successive packages. More generally, we can expect to see new sanctions focuses, especially:

- Extending designation lists for pre-existing types of targets,

- Shortening timetables for implementing some existing bans

- Tackling sanctions evasion, particularly through new designations and law enforcement and judicial action

- Practically implementing ‘freeze to seize’ measures

But ‘freeze to seize’ will take time to bear fruit, given that the legal basis for sustainable rather than ad hoc action does not yet exist in the US, Canada, the UK, or the EU, and the process of democratic legislation is typically slow.

Paradoxically, western sanctions in some areas will probably be scaled back to a limited extent, even as the number of designations overall continues to rise. Any oligarch’s successful legal action to remove their name from sanction lists will set a precedent, causing significant problems for the western approach. If talks develop, Russia is also likely to seek concessions on sanctions in exchange for good behavior. There are already indications of this. In November, Russia requested that western countries remove its state agriculture lender, Rosselkhozbank, from designation lists to facilitate exporting Russian foodstuffs deemed critical to easing global food supply chain problems. Such seemingly innocuous ‘goodwill’ quid pro quos are likely to grow, especially around energy supplies, and some will almost certainly be accepted. It remains to be seen how many and how significant they will be, but citizens’ levels of cold and hunger by spring 2023 are the most likely variables to influence western governments’ calculations.

Other 2023 Hotspots: China

2023 will probably see an expanding range of technology and related sanctions against China by the US. It seems unlikely that other western countries will join the US in imposing blanket measures. However, the UK and other ‘Five Eyes’ countries, which have expressed concerns about Chinese industrial espionage, may do so in the future. In parallel, Chinese sanctions against the democratic coalition will likely focus on explicit political and material support for Taiwan. More wide-ranging counter-sanctions using Chinese sanctions laws against US technology businesses seem doubtful in the current environment.

The key factors which could cause a change in this situation in 2023 are China’s position on Ukraine and Taiwan. If China were to begin providing significant material support to Russia, then the US, EU, UK, Canada, and others would begin targeting Chinese firms, government bodies, and officials suspected of being directly involved in providing support. Although targeted sanctions on senior Chinese figures or major government departments seem highly improbable. Such western sanctions would be extensively calibrated, carefully chosen, and intended to be consequential but not provocative. However, Taiwan would present a different challenge, with the democratic coalition’s response varying alongside the nature of Chinese action.

Other 2023 Hotspots: North Korea

North Korea is highly likely to carry on its current path in 2023, with further missile tests and proliferation activities. Having built up a significant cybercrime capability in recent years, it will also continue to launch cryptocurrency heists. However, a prolonged fall in the value of cryptocurrencies might lead to a switch in tactics and a return to focus on stealing fiat currencies, along similar lines to the North Korean attempt to steal $1 billion of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s accounts with Bangladesh Bank in February 2016.

There is little prospect for any improvement in the standoff between western countries and North Korea. The most probable development will be a further worsening of the situation, triggered by any one of a number of North Korean acts – from the testing of a nuclear device to further missile launches close to South Korea and Japan or more open and extensive support for Russia in Ukraine. With the possible exception of a new nuclear test, none of these events will lead to a new resolution at the UNSC because of the block now placed by China and Russia. Consequently, further measures will probably come from western national regimes alone. For the US, with its pre-existing package of comprehensive North Korea sanctions, new additions will probably focus on the expanding area of North Korean cybercrime and cryptocurrency theft. The US can also be expected to look ever more closely at third-country support for North Korean evasion efforts, especially in China and Russia. The EU, UK, Australia, and Japan will also augment their own lists in 2023, with a North Korean nuclear test likely to stimulate the widest range of action.

Other 2023 Hotspots: Iran

Overall, the prospects for Iranian relations with the US and other western countries in 2023 look poor. Positive developments in the Vienna talks remain possible, but the relative gloom of optimists such as EU foreign affairs lead Josep Borrell suggests that they are unlikely. There is considerable distance still between the US and Iran, and in light of the wider political context, the EU and UK seem unlikely to encourage the US to take a risk. The Biden administration will also be increasingly cautious about doing so as of 2023, with Congress finely balanced between the parties and a presidential election coming in November 2024. President Biden will not wish to give his potential opponents a stick with which to beat him or encourage a newly installed and hawkish Israeli government under Binyamin Netanyahu to consider using military force against Iranian reactors. It is doubtful that the JCPOA will be revived in 2023.

On the contrary, it seems more probable that 2023 will lead to the West hardening its position against Iran, with the EU, Canada, and the UK moving progressively towards a more unyielding stance. The Iranian government’s crackdown on its people and its support for Russia are two areas of significant concern that will probably lead it to continue coordinating further new designations in these areas with the US. It is also possible that some western countries will take more action in areas where the US has previously acted alone, such as Iranian support for terrorism. The UK is the likeliest case for future action in 2023, given comments in November 2022 by Ken McCallum, Director General of the UK’s domestic intelligence agency MI5, that Iran had been behind ten plots to kill or kidnap individuals in the UK.

Explore more by downloading our Geopolitics and Sanctions report today

Originally published 18 January 2023, updated 20 March 2023

Disclaimer: This is for general information only. The information presented does not constitute legal advice. ComplyAdvantage accepts no responsibility for any information contained herein and disclaims and excludes any liability in respect of the contents or for action taken based on this information.

Copyright © 2025 IVXS UK Limited (trading as ComplyAdvantage).