This outline of anti-money laundering and anti-terrorist financing (AML/ATF) in Canada summarizes the most recent legislation and changes to AML regulations. This includes the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act (PCMLTFA), FATF’s most recent mutual evaluation, Canada’s improvements in response to FATF findings, the current state of enforcement of anti-money laundering in Canada, and the challenges faced.

What is money laundering?

Money laundering is the practice of concealing the source of money or assets obtained from illegal activities. There are three primary stages of money laundering. These are “placement,” “layering,” and “integration.”

Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index for 2021 cites that between $43 and $113 billion is laundered annually in Canada. To combat this, the Canadian government announced its 2022 budget would include $89.9 million in funding for the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada (FINTRAC), which would be delivered to the agency over five years.

What is terrorist financing?

Terrorist financing is the use of money or other assets to support and enable terrorist organizations to carry out terrorist acts. Terrorist financing differs from money laundering in two main ways:

- The funds can originate from legitimate sources, not just criminal acts

- The end goal is to use the money to implement or facilitate terrorist activities

What is the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act (PCMLTFA)?

The Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act (PCMLTFA) was created to combat laundering the proceeds from criminal activities and terrorist financing. It established FINTRAC and amended specific additional regulations.

The PCMLTFA’s objectives regarding anti-money laundering in Canada include:

- Establishing an agency that is responsible for ensuring compliance with its regulations and dealing with reported suspicious activity

- Detecting and deterring money laundering and terrorist financing activities

- Requiring the reporting of suspicious financial transactions and cross-border movement of currency and monetary instruments

- Facilitating the investigation and prosecution of money laundering and terrorist activity offenses

- Establishing record-keeping and client identification requirements

- Responding to organized crime while ensuring appropriate safeguards for the protection of personal information

- Assisting in fulfilling Canada’s international commitments to participate in the fight against transnational crime

- Enhancing Canada’s capacity to implement targeted measures to protect its financial system

What is the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre (FINTRAC)?

The Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada (FINTRAC) is a financial intelligence unit that facilitates law enforcement agencies in the detection, investigation, and prosecution of money laundering and terrorist financing activities. FINTRAC is also known as the Centre d’analyse des opérations et déclarations financières du Canada (CANAFE) and it was established in 2000 under the PCMLTFA.

FINTRAC is independent of Canada’s law enforcement agencies, police services, and other government entities but is authorized to contact them and disclose financial intelligence. The agency reports to the Minister of Finance, who in turn reports to Canada’s Parliament. Sarah Paquet was appointed FINTRAC Director and CEO in 2020.

Since 2019, FINTRAC’s national security and intelligence activities have been subject to oversight by Canada’s National Security and Intelligence Review Agency and its National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians. FINTRAC is also a member of the Egmont Group of Financial Intelligence Units, an international organization of financial intelligence bodies.

Enforcement of FINTRAC regulations

Since December 30, 2008, FINTRAC has had legislative authority to issue an administrative monetary penalty (AMP) to reporting entities that are not in compliance with Canada’s PCMLTFA, which may result in criminal or administrative penalties.

In 2016, an appeals court ruling stated that FINTRAC’s method of calculating fines was not clear, resulting in organizations being unable to challenge the amount of the fines due to the lack of uniformity in calculating them. A Federal Court of Appeals ruling repealed six violation notices, resulting in FINTRAC not assessing any fines on financial institutions for AML violations between May 2016 and February 2020.

In 2019, FINTRAC conducted a comprehensive multi-year review of its policies regarding administrative monetary penalties, and in June 2020, the PCMLTFA was amended. There were significant changes, including the timing of Suspicious Transaction Reports, tighter restrictions on pre-paid products, and the handling of Virtual Currency transactions.

The revised anti-money laundering in Canada framework also provides a thorough description of the tools and services available to financial institutions to help comply with the regulatory requirements.

The changes implemented by FINTRAC reinforced its power to impose administrative monetary penalties and improve anti-money laundering In Canada. However, both criminal and administrative monetary penalties cannot be issued for the same instances of non-compliance.

FINTRAC’s penalty review has resulted in five documents for use in compliance enforcement matters. These can be accessed at the links below:

- FINTRAC Compliance Framework

- FINTRAC Assessment Manual

- The Administrative Monetary Penalties policy

- Penalty calculation examples

- A voluntary self-declaration of non-compliance policy

The AMP policy includes a two-step process for calculating AMP amounts for violations of the PCMLTFA when FINTRAC determines, in its discretion, to issue an AMP:

- FINTRAC will classify the violation and assess the harm done. Harm is defined as the degree to which a violation interferes with achieving the objectives of the PCMLTFA or FINTRAC’s ability to carry out its mandate.

- FINTRAC will assess the reporting entity’s compliance history. Penalties for first-time violations will generally be reduced by two-thirds of the base amount. Penalties for second-time violations of the same type will generally be reduced by one-third of the base amount. Penalties for third-time violations will be assessed at the full base amount.

The voluntary declaration of non-compliance policy provides that where the declared non-compliance issue is not a repeated instance of a previously voluntarily disclosed issue – and the declaration has not been made after the reporting entity has been notified of an upcoming examination – FINTRAC will not issue an AMP.

Criminal penalties for non-compliance with FINTRAC regulations

FINTRAC may disclose cases of non-compliance to law enforcement for prosecution when there is extensive non-compliance or little expectation of immediate or future compliance. Criminal penalties (as of 2016) may include the following:

- Failure to report suspicious transactions: up to $2m and/or 5 years imprisonment

- Failure to report a large cash transaction or an electronic funds transfer: up to $500,000 for the first offense, $1m for subsequent offenses

- Failure to meet record-keeping requirements: up to $500,000 and/or 5 years imprisonment

- Failure to provide assistance or provide information during compliance examination: up to $500,000 and/or 5 years imprisonment

- Disclosing the fact that a suspicious transaction report was made, or disclosing the contents of such a report, with the intent to prejudice a criminal investigation: up to 2 years imprisonment

Harm done assessment guides

FINTRAC has published guides that explain the harm done criteria and the base penalty amount for violations under the PCMLTFA and its regulations. These guides are available on its website at the links below:

- Guide on harm done assessment for compliance program violations

- Guide on harm done assessment for large cash transaction reports, electronic funds transfer reports, and casino disbursement reports violations

- Guide on harm done assessment for suspicious transaction reports violations

- Guide on harm done assessment for “Know your client” requirements violations

- Guide on harm done assessment for record-keeping violations

- Guide on harm done assessment for money services businesses registration violations

- Guide on harm done assessment for violations of other compliance measures

FATF mutual anti-money laundering in Canada evaluation report

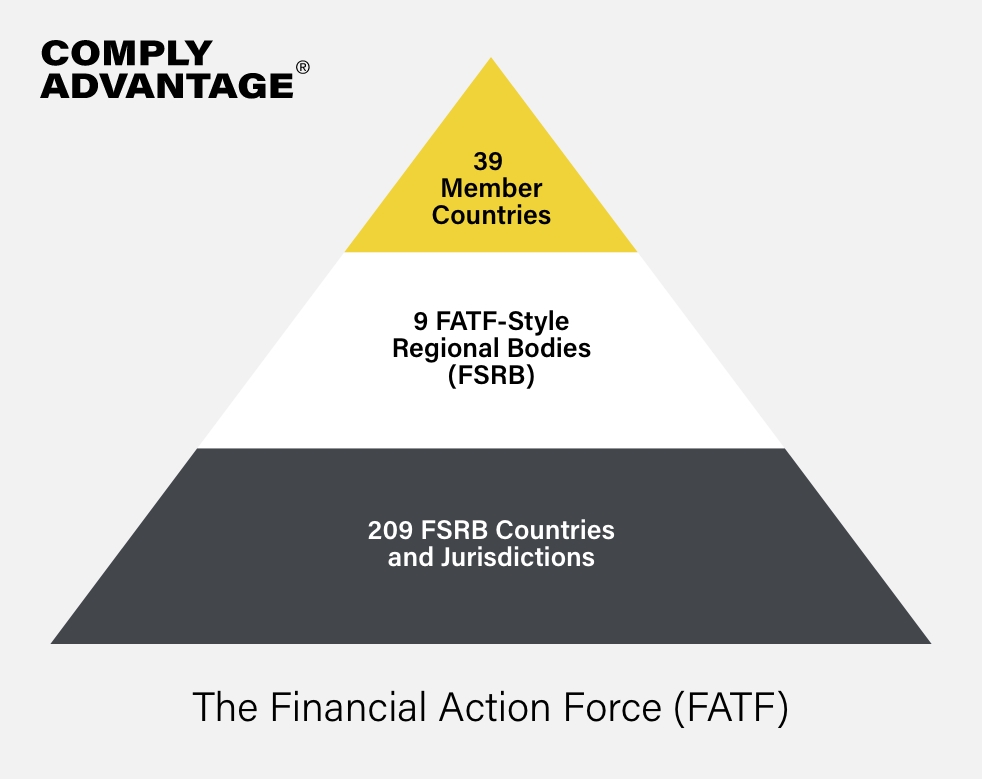

The Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering (FATF) is an independent international body that develops and promotes policies to protect the global financial system against money laundering, terrorist financing, and related threats. There are currently 39 members of the FATF, 37 jurisdictions, and two regional organizations (the Gulf Cooperation Council and the European Commission).

In recent years, FATF recommendations have adapted to mitigate increasingly sophisticated techniques, including the increased use of legal entities to disguise the ownership and control of illegal proceeds and the increased use of professionals to provide advice and assistance in laundering criminal funds.

In September 2016, Canada’s measures to tackle AML/ATF was assessed. This mutual evaluation found that Canada had a robust regime, which achieved good results in some areas but required further improvements to be fully effective.

Findings and recommendations for improvement relating to anti-money laundering in Canada included:

- AML/ATF measures covered all high-risk areas except legal counsel, legal firms, and Quebec notaries. This was deemed to be a significant deficiency in Canada’s AML/ATF framework

- Law enforcement results were not commensurate with the money laundering risk, and asset recovery was low

- Financial Institutions (FIs), including the six domestic systemically important banks, understood their risks and obligations well and generally applied adequate mitigating measures. However, this was not true for Designated Non-Financial Businesses and Professions (DNFBPs), where reporting of suspicious transactions by bodies other than casinos was very low

- FIs and DNFBPs are generally subject to appropriate risk-sensitive AML/ATF supervision, but supervision of real estate businesses and dealers in precious metals and stones (DPMS) was not entirely commensurate to the risks in those sectors

- There was a high risk of misuse by legal persons and arrangements, and that risk was not mitigated

Changes to anti-money laundering measures in Canada

Following the 2016 FATF assessment, Canada has taken several actions to strengthen its framework.

A November 2018 report of Canada’s Standing Committee on Finance recommended the creation of a “pan-Canadian beneficial ownership registry” of all legal persons and entities, including trusts, who have significant control.

Changes were also made to the PCMLTFA in June 2018 to bring anti-terrorist financing and anti-money laundering in Canada in line with FATF standards. These were revised after rounds of consultations.

Changes effective from June 2019 include:

- Allowing the use of scanned or photocopied documents

- A criminal code change to prohibit moving money on behalf of another person if you are aware that there is a risk that the funds could be from money laundering activities

- An alert memorandum to help casinos identify and report suspicious transactions related to the casino business

- A requirement for FINTRAC to make all monetary penalties public

Additional changes effective June 2020 include:

- The requirement for cryptocurrency dealers to register as money services businesses and comply with legislative obligations required of financial institutions

- New rules for cross-border currency and monetary instruments reporting

- Virtual currency obligations for all REs, including submitting Large Virtual Currency Transaction Reports (LVCTRs) to FINTRAC

Other amendments to improve anti-money laundering in Canada, effective June 2021, include:

- The definition of “business relationship” applies to the real estate sector, requiring real estate developers, real estate brokers, and sales representatives to comply with the client identification requirements under the PCMLTFA and its associated regulations. The intent is to continue exempting low-risk accounts from the formation of a business relationship, and exceptions that were previously included in the definition of business relationship have been restated for clarification

- Customer due diligence requirements and beneficial ownership requirements apply to all REs, including accountants and accounting firms, British Columbia notaries, casinos, departments and agents or mandataries of His Majesty, dealers in precious metals and stones, and real estate brokers, sales representatives, and developers

- The time for submitting a suspicious transaction report (STR) has been substantially reduced from “within 30 days” of determining that the activity is suspicious to “as soon as practicable” – additional information is also required in the STR

- A terrorist property report is required to be filed “immediately”

- Domestic and foreign businesses that deal in virtual currency need to fulfill certain AML/ATF obligations, including registering with FINTRAC and implementing a full compliance program. There are limited exceptions, for example, for businesses that deal only in virtual currencies that are not convertible to traditional currencies (closed-loop virtual currencies)

- Foreign MSBs that do not have a physical presence in Canada but which service Canadian customers via the internet or fintech transactions are now regulated by Canadian regulations and are required to comply with the PCMLTFA and its regulations

- The travel rule requires REs (financial entities, MSBs, and casinos) to obtain and record the client’s name, account number, and address. It requests international EFTs and to take “reasonable measures” to ensure that incoming international EFTs also include that information. The amended rule extends those requirements to the beneficiary of international transfers, which may be different from the recipient

- REs are also required to take “reasonable measures” to ensure that any transfer that is received by the RE includes information regarding the requester and the beneficiary

- Securities dealers have to keep records of no more than three people, as opposed to all persons, authorized to access a business account, consistent with the requirement for financial entities

- Prepaid payment products and accounts obligations for financial entities

- Identity verification is required once a credit card is activated, instead of when it is issued, to match the requirements for prepaid payment product accounts

- Casinos must comply with customer due diligence requirements that meet FATF standards and help improve anti-money laundering in Canada

- REs do not have to conduct a PEP determination for certain low-risk entities and accounts (such as a corporation or trust that has minimum net assets of $75m and whose shares or units are traded on a Canadian stock exchange, which is unlikely to be a PEP)

- A PEP check must be conducted for all persons who send or receive $100,000 or more via EFT or virtual currency, or who make a payment or transfer of $100,000 or more to a prepaid account, such as a prepaid card

- REs are required to determine a PEP’s “source of wealth” rather than only determining the source of funds deposited into the account

- Life insurance businesses that provide loans against the cash surrender value of policies or issue pre-paid products are required to comply with PCMLTFA and the enacted Regulations

2021 FATF Enhanced Follow-up Report

In response to measures taken, FATF’s Enhanced Follow-up Report of Canada in October 2021 re-rated the country on several recommendations:

- Politically exposed persons (PEPS) – from non compliant to largely compliant

- Wire transfers – from partially compliant to largely compliant

- Reliance on third parties – from non compliant to compliant

- Reporting of suspicious transactions – from partially compliant to largely compliant

- Designated non-financial businesses and professions (DNFPBs): customer due diligence – from non-compliant to partially compliant

- DNFPBs: Other Measures – from non-compliant to largely compliant

- Non-profit organizations – from compliant to partially compliant

- New technology – from non-compliant to largely compliant

As of 2021, Canada is compliant with 11 of the 40 Recommendations and largely compliant with 23 of them. It remains partially compliant on five Recommendations and non-compliant on one.

The FATF agreed to move Canada from enhanced follow-up to regular follow-up. Canada will continue to report back to FATF on its progress.

Enhancing investigations and law enforcement effectiveness

While amending AML laws to keep pace with criminal trends and FATF updates, investigators have been given larger budgets to strengthen anti-money laundering in Canada regulation and enhance law enforcement effectiveness.

Canada has also created a financial crime compliance and an investigations task force to broaden investigative resources, effectiveness, and outcomes to detect and halt large money laundering networks.

FINTRAC plans for 2022-23 include:

- Generating and disclosing actionable financial intelligence to support major, resource-intensive investigations and hundreds of individual investigations at municipal, provincial and federal levels. These include those conducted by law enforcement, national security agencies, Revenue Québec and the Competition Bureau

- Strengthen collaboration and build innovative partnerships with stakeholders, with a priority on supporting public-private partnerships (PPPs), and Government of Canada priorities, such as combatting the laundering of proceeds of crime derived from human trafficking

- Engage actively with the Financial Crime Coordination Centre (FC3), which brings together dedicated experts from across intelligence and law enforcement agencies

- Develop and disseminate strategic intelligence assessment products to inform the public, reporting entities, authorities engaged in the investigation and prosecution of money laundering offenses and terrorist activity financing offenses, and other stakeholders of specific areas of money laundering and terrorist financing risks

- Explore new analytical methods to maximize the use of existing data holdings and seek to augment data sources to enhance its strategic intelligence products

- Deepen efforts to understand and explore opportunities for enhanced information sharing within the federal AML/ATF Regime

- Operationalize its International Strategy through active engagement with strategic international partners to assist in the development and establishment of AML/ATF standards

Advances in anti-money laundering regulations in Canada

The federal government, provinces, and territories share responsibility for corporate governance on anti-money laundering in Canada.

In 2018, the Canada Business Corporations Act CBCA was amended to require privately held, federally incorporated corporations to create and maintain a register with certain information about their ISCs.

In 2019, to enhance the availability of beneficial ownership information to certain authorities, the CBCA was further amended to require these same corporations to make their registers of ISCs available to certain investigative bodies upon request (subject to certain conditions). Federal, provincial, and territorial governments also reaffirmed their commitment to action on beneficial ownership transparency.

In April 2019, British Columbia became the first province to introduce its own legislation to require registers of beneficial ownership information for provincially incorporated companies, effective from May 2020.

In 2022, the Cullen Commission Report was released detailing findings of money laundering in British Columbia that argued that the federal anti-money laundering regime was “not effective”.

The Financial Crime Coordination Centre (FC3) and the Canadian Financial Crimes Agency (CFCA)

To help combat financial crime in Canada and bolster the country’s response to complex and fast-moving financial crimes through stronger coordination, the Canadian government has committed to developing two new financial crime agencies.

- The Financial Crime Coordination Centre (FC3) was established by FINTRAC to bring together dedicated experts from across intelligence and law enforcement agencies to strengthen inter-agency coordination and cooperation and to identify and address significant money laundering and financial crime threats.

- The Canadian Financial Crimes Agency (CFCA) will become the lead federal enforcement entity responsible for investigating complex crimes and will conduct a comprehensive review of the AML/TF Regime to address any gaps. The agency will work alongside FC3, meaning further regulatory changes are likely to materialize in the coming year.

Improved transparency to increase anti-money laundering in Canada

Most Canadian businesses are honorable and law-abiding. They are supported by a robust governance framework that prioritizes ease of doing business and promotes economic growth. However, some businesses are vulnerable to exploitation by individuals seeking to conceal ownership and control for illegal purposes, including ML/TF and tax evasion.

International and domestic events have emphasized how enhanced transparency of the ownership and control of businesses and arrangements can strengthen law enforcement efforts to prevent the misuse of legal entities.

For example, leaks such as the Pandora Papers in 2021 and the Panama Papers in 2016 highlighted the ease of use of corporations and other legal entities to evade or avoid taxes, facilitate criminal activities, and conduct corrupt activities.

Changes for crowdfunding, FinTechs, and payment services providers

In April 2022, regulations amending the PCMLTF came into force.

The changes affect AML/ATF compliance obligations for businesses in the crowdfunding, FinTech, and payment service provider (PSPs) sectors and aim to meet FATF recommendations regarding the development of new products and business practices.

The changes mean:

- All crowdfunding platform services (CPS) that operate in Canada or foreign CPS that direct and provide their services to persons or entities in Canada must register as MSBs and report to FINTRAC. This includes reporting suspicious and large-value transactions (fiat and virtual currency), record keeping, and KYC obligations. They must also develop a compliance program

- The ‘merchant processing exemption’ has been removed from the definition of an electronic funds transfer (EFT) definition. This means that certain PSPs facilitating EFT must register with FINTRAC as MSBs, institute a compliance program, report suspicious transactions and observe other applicable AML/ATF obligations

- MSBs and foreign money service businesses may see an increase in the scope of reportable activity, as the definition of EFT now includes transactions carried out by credit/debit cards, where there is an agreement by the recipient of the funds with a payment services provider

- A new monetary penalty relating to record-keeping by crowdfunding platforms and arising from crowdfunding platform services has been added

FINTRAC has published commentary to help businesses assess the impact of the amendments and improve anti-money laundering in Canada.

Supplementing these 2022 changes is an infusion of $89.9m over five years to support FINTRAC and the acceleration of the initiative to implement a publicly accessible beneficial ownership registry for federal companies in Canada by the end of 2023.

Areas not covered by anti-money laundering regulations

It is worth noting that most Canadian AML/ATF laws do not apply to attorneys and law firms. A Canadian Supreme Court decision in 2015 found that AML/ATF reporting requirements could violate attorney/client privilege, effectively excluding lawyers and law firms from the need to comply with these requirements with respect to their clients. To date, no legislation has been passed that addresses this issue.

Meanwhile, to curb financial crimes in the real estate sector, the Canadian federal government intends to extend the PCMLTFA requirements to all businesses conducting mortgage lending in Canada by 2023.

How to Choose an AML Software Vendor

10 Factors to Consider Before Building a Transaction Monitoring Solution

Disclaimer: This is for general information only. The information presented does not constitute legal advice. ComplyAdvantage accepts no responsibility for any information contained herein and disclaims and excludes any liability in respect of the contents or for action taken based on this information.

Copyright © 2025 IVXS UK Limited (trading as ComplyAdvantage).