InsurTech Financial Crime Guide: Tackling Risk and Regulation

Learn about financial risks for InsurTechs vs legacy firms, global regulatory trends, and how innovation can help meet compliance challenges.

Download nowMoney laundering, or the processing of illegally obtained funds to make them appear legitimate, is big business. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime estimates the total annual value of laundered money at 2–5 percent of global GDP, or around $2.2 trillion–$5.5 trillion.

Firms found to have abetted money laundering, whether deliberately or not, face the steep financial, legal, and reputational consequences of non-compliance with anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) regulations. To avoid these penalties, they should remain alert not only to regulatory changes, but also to how money laundering actually happens. This article explains some of the most common methods.

Criminals have become increasingly sophisticated at using the complex mechanisms of international trade to launder money. Trade-based money laundering (TBML) occurs in several ways, from forging trade documents to misclassifying commodities. Common examples include:

Because it takes place across multiple jurisdictions and involves several different participants, TBML can sometimes be difficult to track. According to the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), the following are all among the indicators of TBML risk:

In our latest State of Financial Crime survey, TBML was mentioned by 51 percent of compliance decision-makers as one of their top financial crime concerns.

A cash-intensive business is one that generates a large amount of its turnover in cash. This category includes retailers such as shops, bars, restaurants, and certain money service providers such as currency exchanges.

These businesses make frequent targets for money launderers because:

Common methods for laundering money via cash businesses include creating fraudulent invoices, transactions, customers, or services to make it look as if money has been earned legitimately.

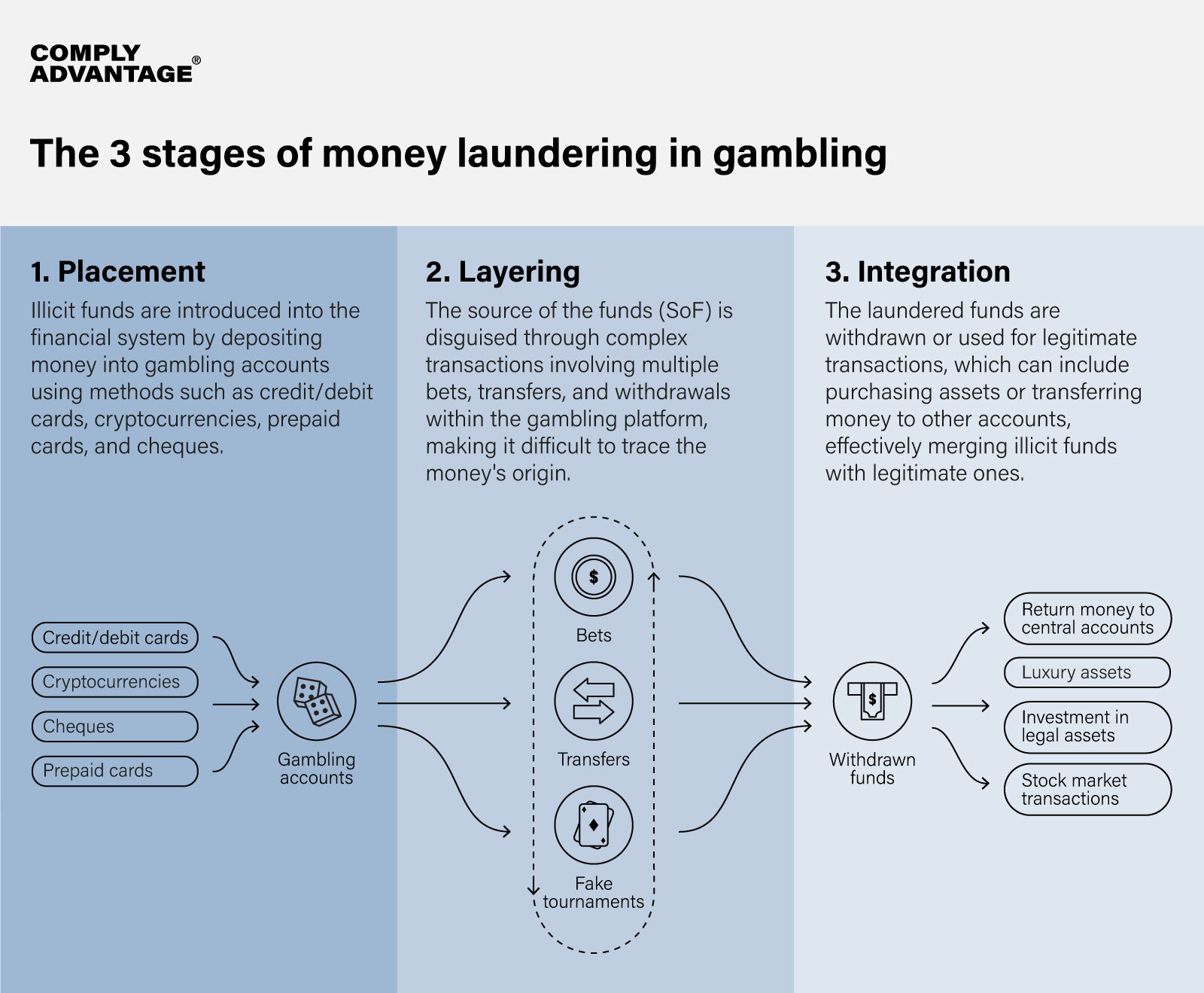

As cash-intensive businesses that allow people to transact large amounts in short timelines, casinos are another common vehicle for money laundering. Unlike FIs that require comprehensive customer identification information, casinos typically collect less detailed data on their customers. As a result, casinos can present criminals with a level of anonymity, allowing them to bypass the stringent monitoring systems of FIs and launder their dirty funds with reduced scrutiny. The use of multiple accounts in online casinos only exacerbates this issue.

In either brick-and-mortar or online casinos, customers can exchange ‘dirty’ money for chips, use these chips to gamble, and then cash them back out to receive ‘clean’ money. Fixed-odds betting terminals are especially common for this method, since they guarantee a relatively small maximum loss for the user compared to more unpredictable games.

Criminals may also deliberately lose money to another player in a game, working as their accomplice, which helps them evade the scrutiny often only triggered by successful bets against the casino itself. There have also been cases of criminals using illegal funds to buy the legitimate winnings of other gamblers at a higher price than the winnings themselves.

Money laundering in the insurance sector involves exploiting the mechanisms of various insurance products to disguise illegal funds. A typical example is premium fraud, where a criminal uses funds to buy an insurance policy – especially a high-value one like life insurance – before requesting a refund or surrendering the policy. This lets them receive some or all of their money back, this time with a ready-made explanation for their source of funds.

Money laundering in insurance may also occur via fraudulent claims to receive payouts of laundered money, or by the incorporation of fake insurance companies to hold and process this money on behalf of criminals in the form of fictitious policies.

Red flags for money laundering via insurance include:

Learn about financial risks for InsurTechs vs legacy firms, global regulatory trends, and how innovation can help meet compliance challenges.

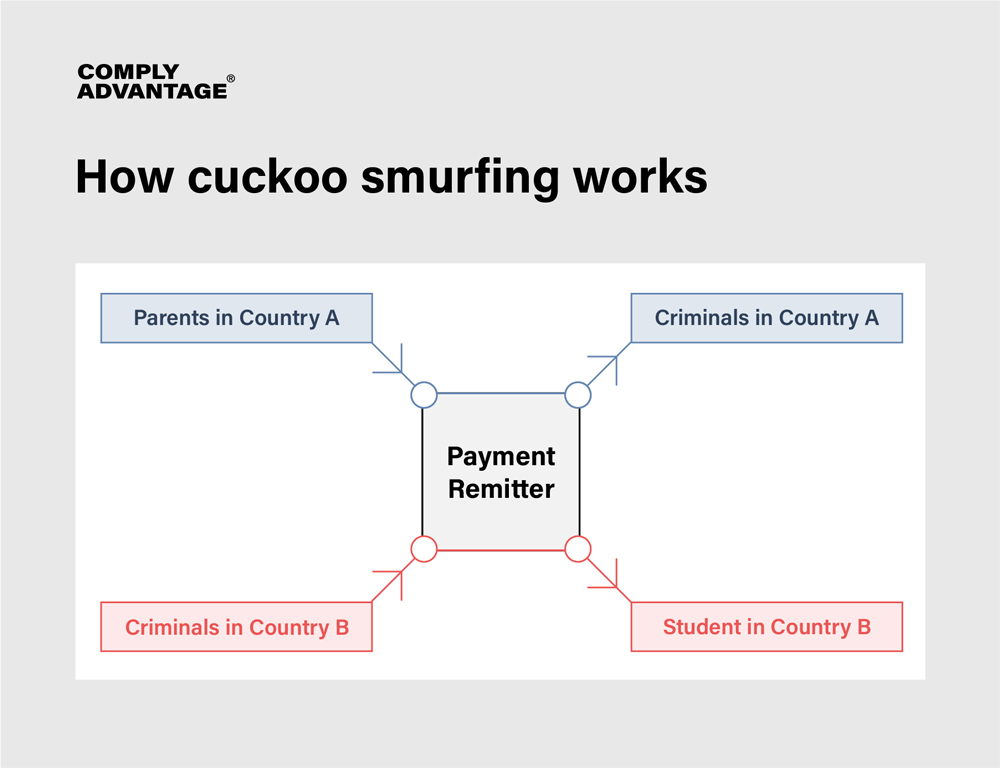

Download nowBasic ‘smurfing’ involves structured cash deposits, under transaction reporting limits, by multiple people, or ‘smurfs’, carrying out transactions on behalf of criminals. The ‘cuckoo’ variant involves using an intended transaction between innocent parties to cover the transfer of value between criminals.

For example, the parents of a student in country A want to send funds to their child studying in country B. In parallel, a criminal group in country B wants to pay the same amount to a criminal group in country A.

The payment remitter processing the transaction arranges for the unwitting parents’ money to be paid into an account controlled by the criminal group in country A, and the funds never leave the country. Meanwhile, funds from the criminal group in country B will be paid into the student’s account. Insiders maintain the relevant paperwork or system inputs to make sure the parent-student transaction appears to have taken place as normal.

A money mule is an individual who has been recruited by criminals, whether knowingly or not, to act as a proxy in laundering money into the legitimate financial system. Typically, a criminal transfers money to a mule’s account before instructing them on how to transfer or withdraw it, often offering a small amount of the money as a reward for doing so. This allows them to conduct transactions while concealing their identity.

Money muling typologies are evolving, often driven by the ubiquity of mobile technology and social media. The FBI has warned that students, jobseekers, and those on dating websites or apps are among the most frequent targets for money muling.

Virtual assets, particularly cryptocurrencies, have become a commonly used tool in laundering money due to the quick and anonymous nature of crypto transactions. Unlike fiat currency transactions, crypto transactions take place between anonymized digital wallets, without the oversight of an intermediary or regulated banking infrastructure. This anonymity makes it easier to move large sums of money without attracting attention.

When funds are traded through several different exchanges for various types of crypto before being cashed out, this creates a particularly complicated network of transactions that can make it challenging to track illicit funds. Because of this, many countries have introduced or extended legislation to make virtual assets explicitly subject to AML/CFT measures.

In 2023, crypto was the most heavily fined industry for AML failures. To mitigate the risk of non-compliance, crypto firms can implement some of the best practices highlighted in the video below.

Peer-to-peer (P2P) money laundering occurs on online marketplaces and other platforms, and exploits the speed of digital payments to structure large amounts of money across several smaller transactions or send money across borders. There are a few different types of P2P money laundering:

The problem of criminal funds flowing into the property markets of major cities has been a growing operational concern among compliance professionals over the last decade, as opaque corporate vehicles are used by anonymous ultimate beneficial owners (UBOs) to buy up prime real estate.

Criminals buy property to store the value of illicit funds or ‘clean’ money by renting or re-selling the property (often with the benefit of the property’s value appreciating over time). Red flags for money laundering in real estate include:

Given the relative ease of manipulating property prices, real estate often represents a particularly lucrative way to launder money, as properties can be under- or over-valued with the help of ‘gatekeepers’ in the sector such as brokers, mortgage advisors, estate agents, and developers. In 2024, the FATF published a review of its members’ compliance relating to gatekeepers, including real estate agents, finding jurisdictions representing more than half of the world’s GDP scored less than 50 percent.

Given the breadth and sophistication of contemporary money laundering typologies, firms should proactively look to minimize their risk of exposure to financial crime. This means:

ComplyAdvantage provides firms access to market-leading data and advanced artificial intelligence (AI) to help them detect and prevent suspicious behavior from across the spectrum of money laundering typologies. Our solutions include:

1000s of organizations like yours are already in the know with ComplyAdvantage’s State of Financial Crime 2025 report. Download your copy now for industry-leading data and expert insights.

Download your copyOriginally published 27 February 2020, updated 11 February 2025

Disclaimer: This is for general information only. The information presented does not constitute legal advice. ComplyAdvantage accepts no responsibility for any information contained herein and disclaims and excludes any liability in respect of the contents or for action taken based on this information.

Copyright © 2025 IVXS UK Limited (trading as ComplyAdvantage).